By Terry Sherwood

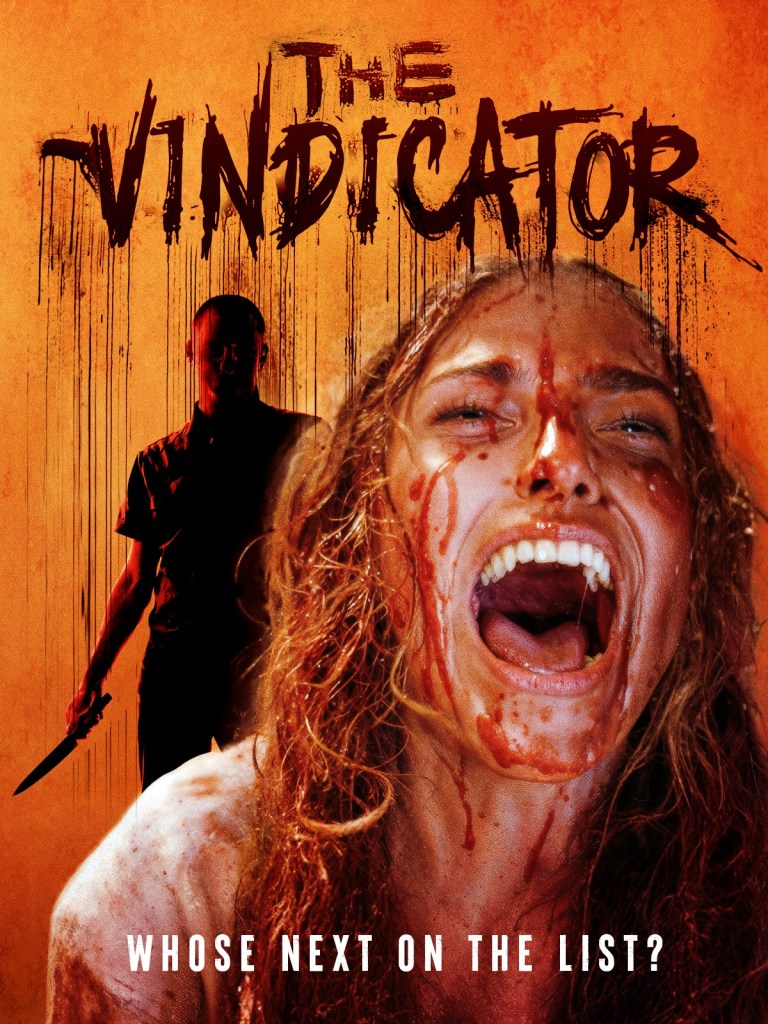

The Vindicator opens with an intriguing, justice-seeking premise the morphs closely into the “Ouji board ‘demon genre that appears. While this is not a supernatural horror more the work us a crime film emerges with moments of gore in a vignette that is built around people speaking on a podcast carefully presenting themselves, shaping narratives, and performing for an unseen audience. When the microphones are shut off, the story pivots into something far more uncomfortable. Real life intrudes, complete with moral compromise, buried guilt, and emotional warts that no amount of self-curation can hide. It’s a compelling setup, one that suggests a horror film interested in accountability and consequence, even if The Vindicator later struggles to fully settle on exactly what kind of horror experience it wants to be

At its core, The Vindicator feels designed for what might be called the “podcast generation.” A significant portion of the film relies on table discussion confessionals, explanatory dialogue, and characters articulating their emotional states rather than allowing tension or atmosphere to speak for them. This approach isn’t inherently wrong, but it drains momentum from a genre that relies heavily on dread, escalation, and visual storytelling which film is . The pacing suffers as a result, becoming flat and overly conversational, particularly in the first half.

Ironically, the film improves noticeably when it abandons this tendency. When The Vindicator shifts into moments of gore, physical threat, and direct confrontation, it becomes more engaging. Not because it suddenly becomes terrifying as true terror remains elusive but because the characters are finally forced into relationships all be it one note relationships. The violence functions less as shock and more as a catalyst, revealing guilt, shared history, and buried secrets.

The central mystery, an unnamed shared secrets weighing heavily on multiple characters should be the engine driving the narrative. Instead, it often feels like a burden imposed rather than explored. You do one thing in your life in your life wrong is the premise. Steve Hendricks and David W. Rice play their roles with commitment, but the secrecy that supposedly binds and crushes them is difficult to fully accept, largely because it is wielded as a blunt instrument rather than something allowed to unfold naturally and it only one flaw. Their characters spend too much time fighting one another when logic suggests cooperation would be the more compelling—and believable—response.

This becomes especially frustrating once the controlling force of The Vindicator is revealed through question-based traps that unmistakably echo the ‘Saw ‘franchise. While the homage is clear, the film never fully justifies why the characters remain so divided under shared threat. The mechanics demand collaboration, yet the screenplay insists on internal conflict, undermining tension and plausibility.

Sean Berube’s Lance is positioned as a physical menace, and Berube delivers the necessary intensity. However, the character never fully dominates the narrative space he occupies. The result is a villain who feels conceptually strong but dramatically underutilized.

Where The Vindicator truly shines is in its performances, particularly Anna Greene. She is, without question, the film’s standout. Her physicality, subtle native born accent on word endings and command of the camera elevate every scene she appears in with help of the chemistry. There is an ease to her presence that contrasts sharply with the film’s structural awkwardness. Simply put, the camera loves her, and the film is better whenever it allows her to lead rather than explain.

The rest of the cast performs well, even when the dialogue works against them. Some lines buckle under the weight of forced exposition or overly explicit emotional confession, yet the actors push through with sincerity. This is not a poorly acted film it is one constrained by a script with some off the wall character changes that suddenly happen.

The final epilogue is perhaps the most puzzling element. It feels unnecessary, tacked on either to increase runtime or to justify additional funding. Rather than deepening the story, it dilutes what little resolution the film achieves, leaving the impression of obligation rather than intention. Seems like the murder house vignette to be added on as the film and direction changes instead of being seamless.

In the end, The Vindicator is not dull, but it is confused. It gestures toward psychological horror, social commentary, and survival-game brutality without fully committing to any of them. There is talent here on both sides of the camera, but the film never quite aligns its strengths or pick which style it wants to be.

The Vindicator is available on digital from 19 January from Miracle Media.