By Terry Sherwood

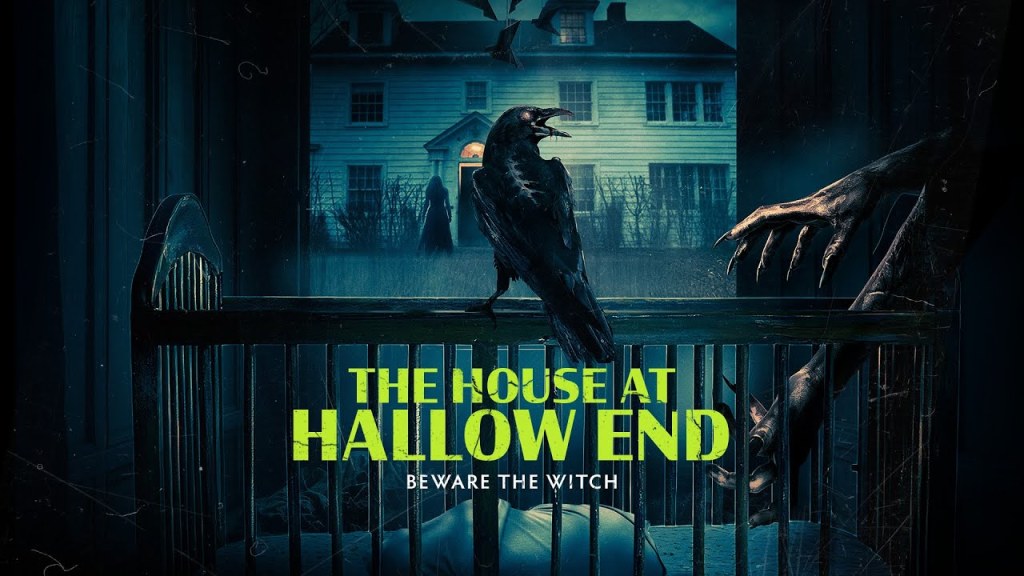

Angela Gulner’s debut feature, The House at Hallow End was originally titled The Beldham opens with inventive promise and atmosphere. The first moments are shaped and quietly unsettling as Harper (Katie Parker) arrives with her infant daughter Christine to help her mother Sadie (Patricia Heaton) renovate a weather-beaten house. The details are small such as a locked door that won’t budge, a crow appearing and vanishing, shadows that linger too long, and the eerie flicker of a beaked figure explained as a taker of infant souls on the baby monitor.

Yet as the picture moves toward its conclusion, the focus begins to drift. Everything becomes so low-key from the subdued acting to the muted emotional rhythms that the tension dissipates instead of escalating. The story circles familiar tropes without sharpening them, creating the sense that the film runs about fifteen minutes longer than needed. The initial promise of forward momentum gives way to repetition, and the narrative loses some of the intensity

One of the more engaging relationships is between Harper and Bette (Emma Fitzpatrick), the young home aide unexpectedly living with Sadie. What begins as a surprise presence evolves into companionship. Fitzpatrick’s Bette is not merely a helper; she becomes Harper’s emotional anchor, the only person who truly listens. When Bette reveals that she herself is pregnant and likely to become a single mother, a natural bond forms between the two women. Their shared fears, hopes, and anxieties create some of the film’s most grounded and sympathetic scenes such as finding something in the garden. Fitzpatrick brings warmth and steady presence, counterbalancing Harper’s mounting uncertainty.

The folk creature known as the Beldham is an bird like being said to prey on infants’ hovers at the margins. Its presence appears in fleeting glimpses: a beak-like face in the shadows, a caw echoing through hallways, a suggestion of talons on the periphery and wounds. . These elements work well individually but lack cumulative intensity.

Katie Parker credited earlier as Catherine Parker, is no stranger to haunted spaces, having appeared as one of the spirits in Mike Flanagan’s acclaimed TV adaptation The Haunting of Hill House. She brings a tender, wounded quality to Harper, capturing a woman struggling to distinguish between postpartum distress and supernatural threat. Yet the screenplay confines her to a reactive mode. Much like Deborah Kerr in Robert Wise’s The Haunting, from the Shirley Jackson novel The Haunting of Hill House. Parker’s character spends most of the film responding to external forces rather than shaping her own path. Kerr elevated this passivity into tragic interiority; Parker comes close, but the script rarely allows her to fully express the turmoil simmering beneath.

Patricia Heaton and Corbin Bernsen, as Sadie and her companion Frank, offer a dynamic that faintly echoes Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. They are not malicious, but the way they hover, soothe, and redirect feels reminiscent of Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer’s Castavets who were helpful on the surface yet oddly intrusive, fostering an atmosphere where Harper can’t quite trust what she’s being told. Their presence adds a subtle layer of paranoia, reinforcing Harper’s sense of isolation in a home where everyone seems to know more than she does.

The work draws strongly from The Babadook but also draws light comparison to Roman Polanski’s Repulsion. Like Carol, Catherine Deneuve’s withdrawn protagonist, Harper becomes trapped in a psychological maze where sounds warp, spaces distort, and reality frays at the edges. Moments of delusion and detachment .Harper’s quiet unraveling alone with her thoughts, her memories, and the house’s oppressive silence evokes that same claustrophobic descent.

Technically, the film looks good. The sound with precision: soft scratches, sudden caws, low ambient pulses. The cinematography favors lingering shots down hallways and empty rooms, capturing the house as a space filled with unspoken history rather than overt threat. The restraint is commendable; the film never reaches for cheap scares. One continuity moment stood put for me in scene with Harper, holding her child confronting her mother and Frank. The child has a magically appearing pacifier in a two shot with child in profile then suddenly the pacifier shows up.

The twist, when it arrives, reframes the haunting as something more sorrowful than sinister. For some, the emotional impact will be strong as it’s a different kind of ghost. For others, the lack of escalating tension may leave the revelation feeling muted. The House at Hallow End remains a thoughtful entry in grief-horror touching, atmospheric, and at times deeply human.