By Terry Sherwood

There’s a kind of horror in watching someone lose control—not to demons or masked killers, but to quiet, everyday indifference. The Rule of Jenny Pen leans hard into that fear. It’s a psychological thriller rooted in helplessness, carried by two exceptional lead performances and one deeply unsettling supporting turn. The atmosphere is suffocating, and it’s meant to be.

Geoffrey Rush plays Judge Stefan Mortensen, a man who spent a lifetime upholding the law, only to find himself in a place where justice means nothing. A stroke—depicted with jarring suddenness—leaves him partially paralyzed and confined to a nursing home. But this isn’t a place of healing. It’s a space ruled by Dave Crealy, a fellow resident who has turned it into a theater of psychological torment.

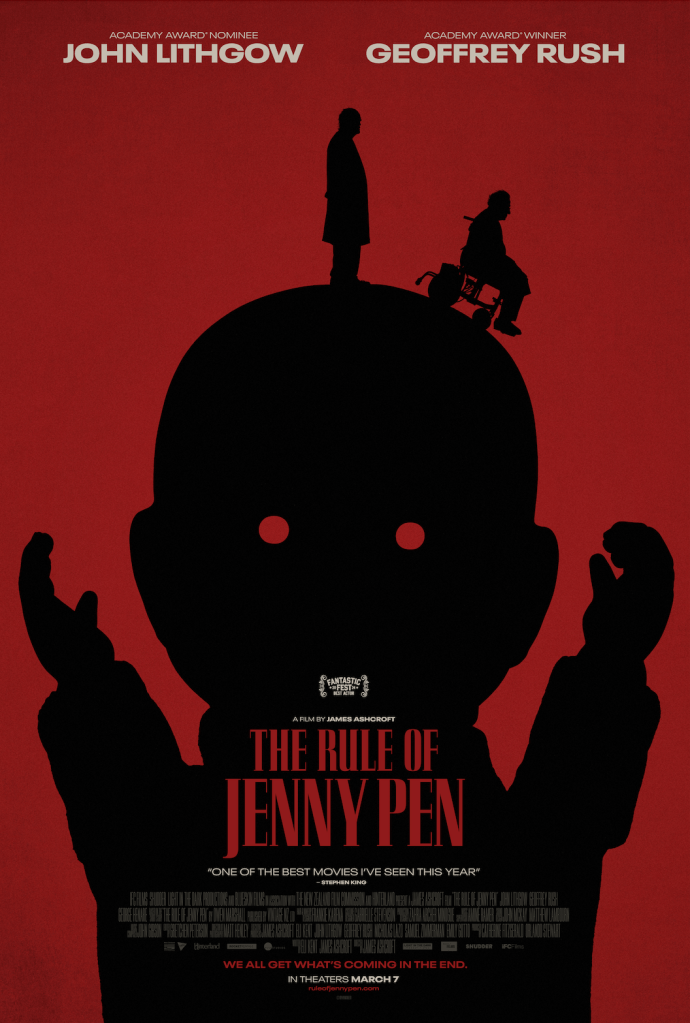

John Lithgow’s Crealy is chilling. He plays the character with a twisted charm, never tipping into cartoonish villainy. His weapon: a puppet named Jenny Pen, both a literal tool and a symbol of his control. Crealy doesn’t just scare—he dominates, humiliates, and isolates.

This is a New Zealand film, so cast members and references to Māori people, plus the sport of Rugby with an All Blacks banner are part of the story. Nathaniel Lees plays Sonny, a former player who is now older and reduced to hiding in remote linen closets.

The setting—a drab, institutional rest home—is used to effect. James Ashcroft keeps things stripped down. No flashy visuals, no dramatic lighting—just dull hallways, muted tones, and routines that bleed into dread. The cinematography avoids flourishing, and the sound design hums with quiet tension. It’s horror built not on jumps, but on atmosphere.

What sets The Rule of Jenny Pen apart is its realism. There are no supernatural crutches here. Jenny Pen may look like a cursed doll story waiting to happen, but the horror is rooted in neglect, systemic failure, and the silence that enables abuse. The scariest part? It feels plausible. The staff’s indifference, the residents’ fear, the unchecked cruelty—it’s all grounded.

Rush gives a lovely performance. Mortensen is slowly stripped of his dignity. His voice—still strong—is one of the few tools he has left. Lithgow, in contrast, is pure chaos in control: a Janus-faced figure who shifts from charming to monstrous in a breath. At one point, he convinces an older woman to walk to her death with the simple lie that her family is waiting outside. In another, he steals food from more vulnerable residents, like it’s a sport. He’s not invincible—he suffers a medical emergency during one of his acts of torment—but he remains terrifying throughout.

Still, the film has its weaknesses. The unrelenting bleakness, while purposeful, can wear thin. The middle act lingers too long on repetition. Some camera choices border on disorienting without payoff, mirroring Mortensen’s own confusion but feeling overused.

Yet for all that, The Rule of Jenny Pen lands hard. It’s not just horror—it’s an indictment. It challenges how society treats the elderly, how systems fail them, and how easily we look away. There’s no ghost, no demon, no escape hatch. Just reality, turned ever so slightly—and horrifically—askew.

This isn’t horror for thrills. It’s horror with a purpose.

The Rule of Jenny Pen is available now on Shudder.